Recall that in Lecture 4 May describes the problematic field, where there are no pre-given solutions, but rather a variety of ways in which difference can actualize itself into identities. He starts off Lecture 5 recapping how this appears in Narrative Work:

We saw the problematic field defined by the question, How Might I Live? You don’t have a set of solutions sitting there, and you choose one or the other. There’s no discovery going on. You create solutions. And each solution that you seek to create is an experiment.

Building on this process of moving from difference to identities, from problems to solutions, May introduces yet another way to describe the same interplay: The Virtual/Actual.

The actual side is what you see. The virtual is what you don’t see, what is inside the actual that allows it to move to new creations in different ways.

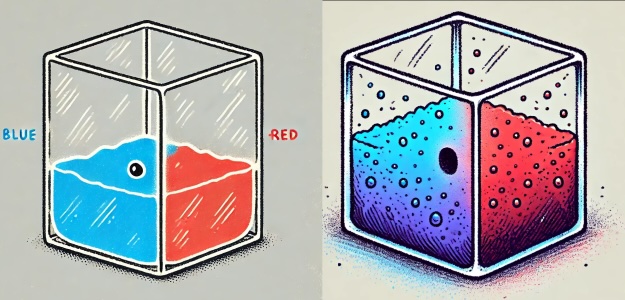

To see this by way of example, May first turns to the work of Nobel prize winning chemist Ilya Prigogine. May says to imagine a box that has a screen in the middle, which is solid except for one small hole. Blue gas enters from the left side, and red gas enters from the right side. May says that for most gasses, overtime the gasses mix through the hole and eventually it all becomes purplish.

But Prygogine says that under certain conditions that are far from equilibrium (meaning intense energy/heat), instead of that movement of red to purplish, something funny happens.

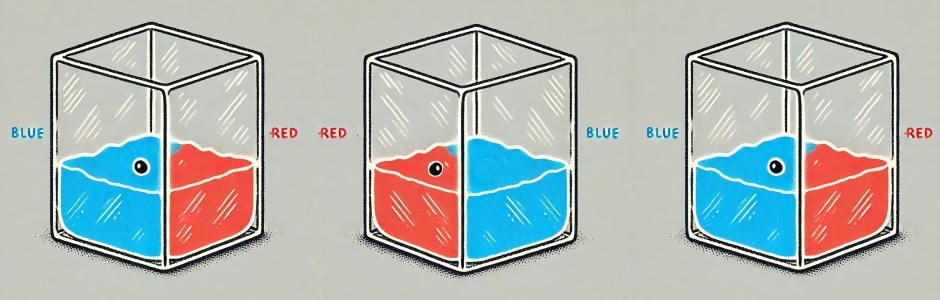

You have, say, the blue over here and the red here, right? And at some interval, it’ll go like that, right? It’ll be blue here and red here. And then at another interval, it’ll go like this, right? And it will keep going back and forth, back and forth, right?

What essentially is happening is at certain periods, the chemicals are coordinating a simultaneous movement across the screen in situations of intense heat. It’s as though the blue chemicals know what’s about to happen with the red chemicals, and the red chemicals know what’s about to happen with the blue chemicals, and they’re like “not yet, not yet, not yet…now!” And then everybody movies.

But what Prigogine says is that the field is somehow structured in such a way that it allows for these strange possibilities, possibilities that don’t exist inside the chemicals themselves, but are merged with the field. So the actual field here is the chemicals — you look and you see the chemicals. But they also constitute a virtual field — a field that can do things under certain circumstances. You can look all day at the actual chemicals and you won’t see the possibility of doing this. That’s the virtual field.

You can also see the virtual/actual at play in a soccer (fine, football) game. You have a bunch of players moving around a field. This is the actual. But the field can unfold in unpredictable ways.

It isn’t just that there’s a bunch of possible plays waiting there, and the unfolding chooses one of them. So it must be that there are various ways in which the virtual field that in a soccer game can actualize itself.

May brings this process back to the individual, who encounters opportunities for actualization through a shock, or crisis.

That shock or crisis, again, doesn’t have to be bad. It’s just something that pulls you to the recognition that there’s more there than what presents itself to you. And Deleuze uses examples of fear, love, the sense of uncanny, being not at home. And you get the sense that there’s more there.

And we use the example from conversational work that you’re talking with somebody, and you engage in this discussion, and things are moving along because you know how this goes. And then something happens, and all of a sudden, you realize, wait a minute. I don’t know how this goes. This is something I haven’t seen before. To follow that, to follow that out, to have that curiosity, is to sense that there’s something more that can be actualized that isn’t an actuality that you’ve already seen.

In his book on Deleuze, May describes “palpating the unknowable”.

There’s something there. You sense it, and the only way to find out – not what it is, because you can’t find out what it is, you can’t represent it, but to find out what it might yield – is to experiment, to follow the experiment, to see where that experiment leads.

May turns to yet another sports example for this experimentation-cum-actualization, this time with hockey great Wayne Gretzky.

He said that when he was really in the zone, he wouldn’t see players. He said there weren’t players on the ice, there were patterns. And he could sense how this pattern might unfold. And so he’d shoot the puck to where he thought somebody in that pattern was going to be. And he was right often enough to be a great player. And so that would be a case where you have an investigation of the virtual to see what other kinds of actualizations might occur.

May then lays out what he calls Deleuze’s fundamental claim – a distinction between the virtual/actual and the possible/real:

Rather than viewing reality as a set of actual structures that have their possibilities, we have to see it as a set of actualities that have woven in a virtual field.

The possible, May says, is some idea that does not exist, but could exist. He gives the example of a closed window..

The possible exists in the image of the real. It’s like the real. Except it’s lacking only one thing. It’s not realized. With the window, the possibility of opening the window exists, and when the window opens, it’s just like its possibility was. But the virtual is not like the actual. The virtual is different in structure from the actual.

Compare the window to the virtual field of the infant’s brain, which May says could develop in innumerable ways, none of which are pregiven. Mays does note, however, that virtual fields do have their contingencies. The infant’s brain could not develop into that of a seagull.

Thinking in terms of unrealized possibilities represents the transcendent, which the Nietzschean Delueze wholeheartedly rejects.

For the philosopher in nature, what was transcendent was God. That was the major transcendence. And what God does is judges us, and finds us inadequate. We are always inadequate. So we have to deny ourselves for the sake of this God to whom we owe everything because God made us. And what Nietzsche says is, what this winds up being is a denial of life.

For Deleuze, and his forebears Nietzsche and Spinoza, everything is imminent.

Rather than denying the world on the basis of some transcendence that judges it, we celebrate the world by experimenting with it because of its structure. The virtual/actual structure is a structure that permits all kinds of creativity. So the imminent view for Deleuze is an ontological structure of joy, that we celebrate in experimenting. Because rather than having this God out there that condemns us, that makes us deny ourselves, we see the world as a world that’s rich with possible creation.

Again, I love the idea of affirming through creativity, and how that contrasts with Hegel’s dialectic, which labors through negation. Moreover, every actualization restructures the virtual. So you don’t have the same virtual after a new actualization. Yet another sports example to illustrate:

A football game unfolds, and there’s a play. After this particular play happens, then you still have the virtual field, but it won’t be structured the same way because it’s within a different actual.

Life as an ongoing creative process – philosophy becomes a project of joy and creativity, emphasizing what can be created more than what can be denied.